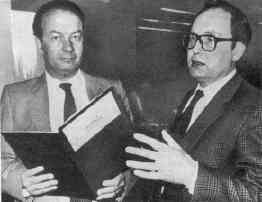

Gerd Heidemann (on the right) stands next to Wolf Hess, son of Nazi leader Rudolf Hess. They hold between them one of the notebooks of the Hitler diaries.

The Hitler Diaries

The fall of the Third Reich created a thriving market in Nazi memorabilia. On April 22, 1983 the German magazine Der Stern announced that it had made the greatest Nazi memorabilia find of all time: a diary kept by Adolf Hitler himself. And this was not just one thin journal. It was a 62-volume mother lode, covering the crucial years of 1932-1945.

The diaries caused a buzz of excitement to sweep through the media. Magazines and news agencies bid for the right to serialize them. Journalists, historians, and World War II buffs eagerly anticipated what insights they would reveal into the mind of the twentieth century's most infamous ruler. Of course, voices of skepticism were raised. Many historians pointed out that Hitler was notorious for not liking to take notes himself, but Der Stern insisted that it was not possible that the diaries were a fraud.

The explanation of where the diaries had come from was plausible enough to be credible, while also being appropriately unverifiable. Apparently during the last days of the Third Reich an airplane carrying many of Hitler's personal effects had crashed near Dresden. The diaries were pulled out of the wreckage of the crash and preserved for the next three decades by an East German general. In the early eighties they were smuggled out of East Germany, one at a time, by the brother of a West German memorabilia dealer named Konrad Kujau. They were then sold to Der Stern through the efforts of their reporter Gerd Heidemann for the astronomical price of 9.9 million marks.

Anticipation continued to build about what the diaries would reveal until experts had a chance to examine them and delivered their unanimous verdict: the diaries were clumsy, almost amateurish forgeries. Physically it was clear that the diaries were fake. The whitener and fibers in their paper were of postwar manufacture. The content of the journals was also a dead giveaway. The entries were stupefyingly dull and trivial, not revealing anything novel about Hitler's state of mind. Moreover, most of the entries had simply been plagiarized from a book called Hitler's Speeches and Proclamations written by Max Domarus, a former Nazi federal archivist. Even historical errors that Domarus had made were sedulously repeated in the Hitler diaries.

Faced with this evidence, Der Stern grudgingly admitted that it had been duped. The source of the forgery was soon traced to Konrad Kujau, the West German memorabilia dealer. He had written the diaries himself, after having perfected the art of imitating Hitler's handwriting. Heidemann was also accused of having skimmed off over 1.7 million of the marks that had been paid for the diaries. Together this pair, Kujau and Heidemann, were convicted of fraud and sentenced to over four years in prison each.

References:

- Ed Magnuson, "Hitler's Forged Diaries." Time. May 16, 1983. p.36-47.