From: Andrew Johnson

Date: 2007-02-02 09:09:25

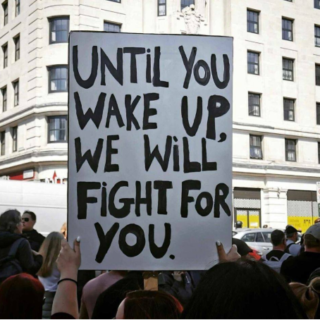

arts.guardian.co.uk/…,,1998179,00.html ‘They’re all forced to listen to us’ It began as a tiny internet film attacking the ‘lies’ surrounding 9/11. Now, millions of people have heard its message. Like it or loathe it, you can’t ignore Loose Change, says Ed Pilkington Ed PilkingtonFriday January 26, 2007 Guardian Four hours’ drive north of Manhattan in the Catskill Mountains, Oneonta is as close to redneck country as you can find in the state of New York. As the road winds upward, the terrain thins out into wooded hills dotted with bungalows, with rusting Cadillacs parked outside. At this time of year, the area should be buzzing with skiers from the city, but El Niño and global warming have put paid to that. In the absence of snow, this famously beautiful part of America looks depressed and down-at-heel. At the end of the journey is a white clapboard cabin surrounded by muddy fields and a couple of dilapidated sheds. Inside, the house is sparsely furnished with plastic chairs and a worn brown carpet. Three young men in their early 20s are sitting around on a futon in the back bedroom watching Family Guy, the animated TV show, on a large plasma screen and playing with a puppy. On the desk in front of them are three computer screens showing, incongruously, the skyline of Manhattan in segments, like a 21st-century triptych. At first glance, this seems an unlikely setting for what can reasonably be called a revolution in film distribution. There is nothing Beverly Hills about this room, or the twentysomethings sitting around in it. But when you stop to reflect, it is the perfect setting for the command-post of a phenomenon that has turned normal movie logistics on their head, challenged assumptions about documentary film-making and journalism, and created an army of hundreds of thousands of devoted “info warriors”. This is the bedroom of Dylan Avery, the director and creator of Loose Change, the most successful movie to emerge from what followers call the 9/11 Truth Movement. More commonly, they are referred to as conspiracy theorists. They believe – or rather, they insist they can prove – that the attacks in New York and Washington on September 11 2001 were not the work of Osama bin Laden, but of elements within the US government itself. They reject the term “conspiracy theorists”, arguing that if you accept the official line on 9/11 you have in any case signed up to a theory about a conspiracy – an al-Qaida conspiracy. Many people find the world of such anti-establishment sceptics, to use polite terminology, deeply suspect and verging on the offensive. A few of the families of the victims of 9/11 have said as much to the Loose Change crew, although Avery says many more have offered support. But push aside any instinctive distrust there might be about what they are saying – we’ll come back to that later – and consider for a moment its impact. The movement of 9/11 sceptics has had an astonishing success in sowing doubt across the US. Recent polls suggest more than a third of Americans believe that either the official version of events never happened, or that US officials knew the attacks were imminent, but did nothing to stop them. That’s an impressive statistic in itself. Now look at the success Loose Change has had. Google Video acts as a portal for the movie, where you can also see the running tally of the number of times it has been viewed since last August. As I write, it stands at 4,048,990. By the time you read this, it will have risen considerably higher. On top of that, the movie was shown on television to up to 50 million people in 12 countries on September 11 last year; 100,000 DVDs have been sold and 50,000 more given away free. Then there are many more who have watched the film but are never counted, as a result of the active encouragement the film-makers give their supporters to burn the movie and distribute it to their friends. Avery says 100 million people – “easy” – have seen it. That may be an exaggeration, but it’s fair to say that something extraordinary is going on. The Loose Change story begins in May 2002 on the opening night of a Mediterranean restaurant in Oneonta where Avery, then aged 19, is working as a dishwasher. A friend of the owner, James Gandolfini (aka Tony Soprano), is a guest at the party and Avery gets chatting with him. “We started talking about movies and shit,” Avery recalls. “Gandolfini told me, if you want to do something that matters, you have to talk to the entire world. You have to have something to say.” Avery had just finished high school. He’d long been a film buff, a fan of Tarantino, Fight Club and The Matrix. He was inspired to begin writing a novel/film-script. He began toying with the idea of a fictional work that would explore the fantasy that 9/11 hadn’t been carried out by 19 Arabs with box-cutters, but by the American government as an attack on the minds of its own people. At that point, he was writing pure fiction. But as he began researching September 11 for background to the story, he began to come across evidence that made him change direction. All the footage and the eyewitness accounts he gathered, he says, “just didn’t add up”. The second of the three twentysomethings enters the scene. He is Korey Rowe, now aged 23 and Dylan’s best friend from Oneonta. Five years ago, Rowe joined the army because he had nothing better to do and he’d heard the golf was good at training camp. Then 9/11 happened and “everything went crazy”. He was posted to Afghanistan for six months and later for a year to Iraq. Rowe extracted himself from the military in 2005 and joined Avery full-time in making Loose Change. By now, it was taking shape as a part fiction, part reality movie, but eventually they decided they had enough material to go all-out as a documentary. The first edition of Loose Change, running at 30 minutes and produced on a battered Compaq Presario laptop (price $1,500), was finished in April that year. The second, longer, edition – the one currently available on the internet – came out in September 2005 with the help of a third partner and fellow Oneonta resident, Jason Bermas, aged 27. Entirely self-taught, and without a single journalistic qualification between them beyond a couple of media courses Jason sat at college, the three men have sought to take on the combined might of the Bush administration, the FBI, the CIA and the mainstream media. If viewer statistics are a measure of success, they have to no small degree prevailed. One can speculate as to the reasons for their success. September 11 was such an overwhelming event that many people have been open to the wilder accounts of what lay behind it. The reaction of the Bush administration – Afghanistan, Iraq, Guantánamo, terror clampdowns within America – have generated profound fears about the president’s intentions. And this openness to – even need for – alternative explanations has come at just the moment when the internet has made it possible for such theories to be disseminated rapidly and widely. The power of the film is that it lays down layer upon layer of seemingly rational analysis to end up with a conclusion many would find incredible. It is compiled from original footage from numerous news sources, narrated in Dylan’s mild, almost monotone voice, and backed by an soundtrack from DJ Skooly and others that induces a sense of the ominous. And so to the message. The Twin Towers in New York didn’t fall as a direct result of the planes hitting them and the fire that ensued; they were brought them down in a series of controlled explosions. George Bush’s brother, Marvin, sat on the board of a company that insured the towers. “I think what happened to the World Trade Centre was simple enough,” Avery says in the film. “It was brought down in a carefully planned controlled demolition. It was a psychological attack on the American people and it was pulled off with military precision.” Flight 77, which supposedly flew into the Pentagon, could not have flown at that speed without going into a tailspin. There is no sign of any parts of an aeroplane in footage of the crash site, and the building looked as though it had been hit by a missile. Meanwhile, Donald Rumsfeld was safe on the other side of the Pentagon. Flight 93, said to have come down in a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, never did crash there. Instead it landed in Cleveland airport shortly after the airport had been evacuated. The emotive phone calls by the so-called passengers to their relatives before they “died” were staged. There are several flaws in the argument. The list of those who would have to have been party to the plot is implausibly long for it to have remained secret, from Bush himself to Rumsfeld and Cheney and the FBI and Pentagon … and on and on. Much of the supporting evidence in the film was taken in the first minutes and hours after the attacks, when confusion reigned. And George Bush may be a disastrous and dishonest president, but would he be capable of such a monstrous act? The three men have instant answers to any objections you can throw at them. There may have been a lot of people involved – they think about 100 – but only a handful of those would have known the full plot. As for Bush acting heinously, haven’t leaders the world over proven themselves capable of monstrous acts? There’s a futility to arguing with them that even they recognise. “You can’t stop this, you can’t hold us back,” Jason says. “Many outlets have tried to ignore us, but in the end they are all forced to listen to us because their viewers are demanding it.” He is right. The exponential growth of Loose Change is gradually forcing the film on the mainstream media. Though it began as an internet phenomenon, its biggest spikes have come, significantly, after the film gained airplay on old media platforms such as Air America and Pacifica radio stations, local Fox TV outlets and on stations around the world, including state outlets in Belgium, Ireland and Portugal. So far though, no British channel has been rash – or as the film-makers would see it, brave – enough to bite. “This is unlike anything I have worked on,” says Tim Sparke of MercuryMedia, which handles international distribution for the film. “It has forced millions of people to question whether they can trust big media, and by bypassing the broadcasters through internet distribution it has altered the media power balance profoundly. With a little money and passion, anyone can make an important film.” The final test for Avery and co is yet to come. They are putting together Loose Change: the Final Cut using an upgraded Power Mac G5 (price $5,000). They have filmed original interviews with Washington players, employed lawyers to iron out copyright issues with borrowed footage, commissioned 3D graphics from Germany, and recruited a theology professor to act as fact-checker and consultant. The end result, they hope, will be seen at Cannes and have a cinema release in America and across the world on the sixth anniversary of 9/11. If that happens, they will have squared the circle. The underground film-makers will have come up for air, exposing millions more people to their argument – and themselves to intense scrutiny. Stand back and enjoy the fireworks. Guardian Unlimited © Guardian News and Media Limited 2007