22 Oct 2017

Andrew Johnson – ad.johnson@ntlworld…. (Edited by Bob Greenyer)

In October 2017, Bob Greenyer of the Martin Fleischmann Memorial Project (MFMP) invited me to view testing of an experimental reactor developed by Dr George Egely. The testing was set to take place at Bob Greenyer’s office in Brno, Czech Republic. Dr Egely had travelled from Hungary, with 2 colleagues who had brought 2 small (almost identical) reactors with them.

The experiments were primarily being done in order to see if one element (carbon), in the presence of air, which contains predominately Nitrogen and Oxygen, could be transmuted into other elements, within the reactor.

MFMP was set up by Bob Greenyer and four other conference Condensed Matter Nuclear Science conference attendees in 2012, in Korea, in order to try and build on the work of Drs Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons by collaborating with researchers who are doing related experiments to the ones done by Pons and Fleischmann in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Pons and Fleischmann discovered a process which became known as “Cold Fusion” and despite successful replications of their work and interest from some areas in academia, they were vilified and even ridiculed for their research. Their research was successfully side-lined and marginalised.

Transmutation

This is the name given to the process of turning one element into another. According to mainstream science (physics), this should not be possible outside of some type of conventional Nuclear Reactor or particle accelerator (like the one at CERN). It was this transmutation of elements, seen in the results of Pons and Fleischmann’s experiments – and similar experiments – which proved the processes involved weren’t just chemical reactions. For example, in experimental cells they and others later ran at Texas A&M, Stanford Research International and ENEA Frascati, elements such as helium and, more importantly, the rare hydrogen isotope tritium were found where there had been none before the experiment was run. Something more complex had produced unknown effects – which they originally thought might be due to nuclear fusion, but they later concluded some other process was responsible). The www.lenr-canr.org website is a good reference if you wish to learn more.

Reactor and Other Equipment

Over the last decade, Dr Egely had designed and built several similar reactors, each of which are relatively straightforward to explain. In very simple terms, the reactor he designed could be described as a “modified microwave oven”. A magnetron tube from, rated at about 1500W, is used to heat material in a small quartz glass “reactor core” to very high temperatures. Where this is different to a normal microwave oven is that the shape of the reactor vessel is chosen so that certain electromagnetic and acoustic resonance effects may occur within the microwave field and quartz core respectively, when the reactor is powered up.

The reactor we tested used a magnetron tube that was powered by a 50 Hz AC supply rectified to 100Hz. It was a very basic unit that was essentially just being used to heat up the sample so much so that it would create a plasma inside the reactor vessel.

Dr Egely has designed the reactor as a stepping stone itowards trying to eventually produce an efficient energy generator, which may ultimately, when fully developed, produce more energy than is put into it. However, the version we used was built primarily to test if we could find evidence of transmutation of elements.

Experimental Procedure

This was quite straightforward. Carbon dust was used that had previously been tested for contamination with other elements which was created by grinding up small ultra-pure spectrographic carbon electrode cylinders (see below) with a pestle and mortar and then sieving this dust to select the finer grains.

This Carbon dust was placed into a quartz glass vessel, along with about a 3cm length of ‘HB’ propelling/mechanical pencil (diameter 0.3mm) and then the magnetron tube was powered on.

Within the reactor, two types of glass vessel were used (see below).

The spherical reactor vessel was moved backwards and forwards in the reactor (relative to the front plate) to get the dust sample in the correct place to get the best heating of the dust (see video). The vessel was tapped with a hard object (penknife blade) to agitate the dust in the reactor vessel.

Precautions had to be taken, because the reactor had a gauze cover at the front, used to enable enhanced visibility, was found to leak out some microwave radiation.

The reactor was powered through a PCE-830 power measurement meter, although this data was not used for our experiments. A clock and a gamma radiation count detector were placed near the reactor. Also, for some runs of the reactor, fast and thermal neutron detectors (nuclear industry standard sealed tubes of a special hyper-critical gel from BubbleTech) were placed near the reactor.

Each run was filmed and live-streamed. The reactor was run for about 3 to 5 minutes until perhaps half or three quarters of the dust had burned. The ash was then removed from the reactor vessel.

In separate runs of the reactor, potassium carbonate (K2CO3) and Copper Carbonate (CuCO3) were added to the carbon dust to see what effects this would have, and what compounds might form during the plasma burning. Bob Greenyer suggested that the potassium carbonate would assist ionisation of the plasma, due to it being able to give up electrons, without it, the spectrographic carbon failed to make a plasma.

Tests Performed

After the reactor and reactor vessel had cooled, the “ash” from the reactor was extracted and placed on white paper (note that this seemed to cause some elemental contamination – see below). The paper was moved over a strong neodymium magnet to check the ash for magnetic properties, as changes in magnetism had previously been reported (see video).

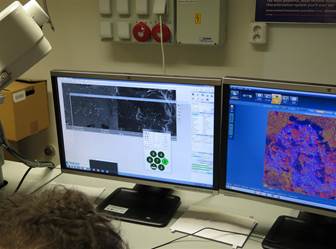

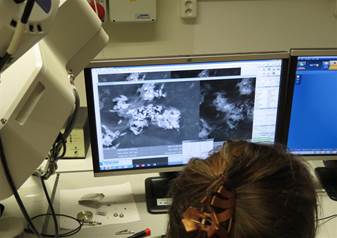

Samples of the ash from each run of the reactor were placed on separate sample pads which were labelled and then placed in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) which also had a built in mass-spectrometer.

Results

Neutrons

No fast or thermal neutrons were detected.

Gamma

No gammas above background were detected.

Magnetism Test

It appeared some small proportion of the dust was diamagnetic (it moved away from the magnet – see video). However, the original spectrographic rods are also diamagnetic.

SEM / Mass Spectrometer

When the powder samples were scanned under the electron microscope and mass spectrometer, as well as the expected elements of C (Carbon), K (Potassium), and Oxygen, small amounts of calcium, aluminium , sulphur and silicon were detected in 2 of the samples, but this was not viewed as conclusive proof that transmutation had occurred.

Coating a sample of paper with gold plasma!

Calcium – The paper was tested under the SEM (after coating with gold!) and found to contain some calcium – probably from some type of “talc” used to whiten it or help the paper flow in the production process or added to help it move more easily through printers or copiers.

Silicon – A sliver of the rubber bung that was used in the end of the spherical reactor vessel was also tested and found to contain silicon. The glass, some of which had cracked or even slightly melted, contained silicon so either or both of these may have provided a contamination source.

Sulphur – Although we couldn’t identify the source of sulphur, it was not present in large amounts in the samples we tested.

Limitations of Experiment Tests

MFMP had to pay an hourly rate in excess of $200 for the hire of the SEM/Mass spectrometer instrument and so we only had a limited time to test each of the samples i.e. if more time had been available, it’s possible that more evidence of transmutation may have been found.

Additionally, participants in the experiment had travelled many miles and so the reactor runs had to be done all in a single day, which meant there was not enough time to revise experiments and procedures based on results obtained in early experiments.

Earlier Results from Dr Egely

Prior to our tests with the graphite powder, Dr Egely had reported much better results with low conductivity charcoal, however charcoal naturally contains some of the elements that can be observed. He had obtained much more iron in the ash, whereas we had found none. Dr Egely also advised us that the reactor he used had a slightly different design, in 2 important areas:

a) The front of the reactor was a solid plate which did not use a gauze (we used this so that the reaction was more visible, however the normal plate does have a number of microwave blocking observation holes)

b) The power supply of his other reactor was more sophisticated and its frequency could be varied.

Dr Egely briefly explained to me that by a careful combination of positioning the reactor vessel, making the reactor vessel of a certain shape and then “tuning” the frequency of the power supply, the reaction could be made much more energy efficient.

He also noted that with a closed reactor chamber, the volume/noise of the reactor in operation was very much louder (perhaps 10 or 20 times louder) than with the reactor we used in our tests, which might be due to loss of microwave energy through the gauze also. Also, using charcoal rather than the carbon dust seemed to produce a more vigorous reaction.

Explanation?

Bob Greenyer suggested reasons why we might not have seen much evidence of transmutation in this case as follows.

1) The main reason is that we used spectrographic carbon powder made from conducting diamagnetic electrodes NOT charcoal – which is more amorphous. The suggestion was that the carbon used was incapable of building up charge. Ken Shoulders has suggested that nuclear effects are caused by charge clusters. Charge clusters need to form in isolation – away from conducting materials (e.g. in air, which is an insulator). Charcoal does not conduct electricity effectively, so it’s possible that it allows charge clusters to form more easily and thus, transmutation effects are seen.

2) Our reactor was different from those formally tested and did not use a resonant/variable frequency power supply. It’s quite possible that resonance effects play a significant role in any processes that results in transmutation.

Further Experiments

At this point, MFMP proposes further experiments, at least using a non-conductive pure form of carbon, an industrial colourant called ‘Carbon Black’ was suggested by Dr. Egely, rather than the spectrographic carbon dust we used. Carbon Black powder is like a purified form of soot, though its actual purity may vary from supplier to supplier. This should be a more suitable candidate for transmutation tests because it is more pure than charcoal (as noted above, charcoal could contain a varying number of other elements which have come from the wood type, or from any equipment used in processing or burning the charcoal.)

Samples will be tested for the elements they contain before being put into the reactor.

More Information from Dr Egely

This can be found in this video, made with Bob Greenyer last year: